- About us

- Contact us: +1.641.472.4480, hfi@humanfactors.com

Cool stuff and UX resources

Introduction

Remember Goldilocks? She's the fairytale girl who visited the three bears' home in the woods, trying out their chairs, beds and then porridge in groups of three. The first chair or bed or bowl of porridge was just too big, hard, or hot. The second was too small, soft, or cold. But the third was, well, "just right".

When researching this on Wikipedia I was amazed to learn there is a "Goldilocks Principle".

(I also learned that our planet is called a "Goldilocks planet".Our planet Earth falls "just right" ‚Äď for example, Earth is neither too far from the sun nor too close to the sun. The Earth's distance to the sun is "just right" for supporting life, our jobs and our mortgages. It all works out.)

Now, how often have you proposed a design that you thought was, well, "great". But your buddy thought differently: "not so great".

Can we apply the Goldilocks Principle to tweak the design so that it's "just right"?

You bet. Let's see how using the Goldilocks Principle benefits us more than plain old usability testing.

Overcoming test anxiety

OK ‚Äď just how good do you feel about testing as a tool for iterating your designs?

If you're like me, testing designs can be a bit like asking somebody out for a date. What if I get rejected? Dark thoughts intrude...

And I'm sure when you finish each design you just "know" it's going to work. But what if it doesn't?

This process of testing while designing is called "formative testing". We test while still "forming" our approach to solving the design problem. This contrasts with "summative testing" that we conduct on our finished product.

And that's the point. With formative testing, we need to remember that we really have not completed our design until we test it, iterate, and test again.

This attitude takes us out of the dating metaphor where dark thoughts can hamstring our efforts to move forward with creative alternatives.

Instead, we move into the Goldilocks Principle as our guide to design practice. With the Goldilocks Principle, we test in order to get it "just right." The Goldilocks Principle can replace the judgmental attitude that is often associated with testing.

Let's see how the Goldilocks Principle can apply to testing aesthetic design decisions.

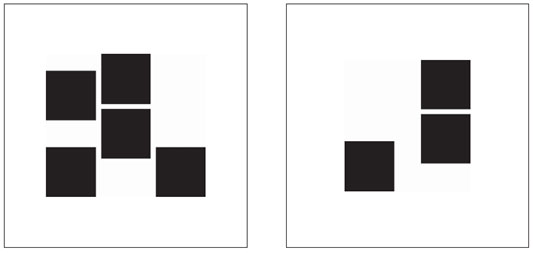

Figure 1. Example stimuli from Experiment 1. Shown are the benchmark image (left) used for comparison and one of the 27 test images (right) rated by the participants.

Figure 2. Example from experiment 2. Participants compared the aesthetic appeal of 27 layouts (such as on the right) with the single benchmark (on the left ‚Äď with a score of "10"). If the layout on the right appeared twice as appealing, it got a score of "20".

Aesthetic evaluation and the Goldilocks Principle

Two University of Michigan researchers, Michael Bauerly and Yili Liu wondered how to design layouts on web pages to maximize the "aesthetic preference". They varied two important components of layouts: symmetry and the number of compositional elements.

In their first experiment, they used black squares on a white background and asked their 16 participants to compare each of 27 designs to a "benchmark" design (on the left). The benchmark design got an arbitrary score of "10".

If a participant felt the design on the right was twice as appealing, then it got a score of 20. If it was considered half as appealing, it got a score of 5. The authors called this a "magnitude estimation method" ‚Äď not a bad technique for usability testing.

I will report their results from their second experiment, a replication of what we just saw, but with images created to look like Web page screenshots.

Before we continue, make a guess regarding how many elements (on the right) participants would tolerate before giving the design a lower aesthetic appeal ‚Äď 3? 5? 7?

Or, are they equal in appeal?

Getting it "just right"

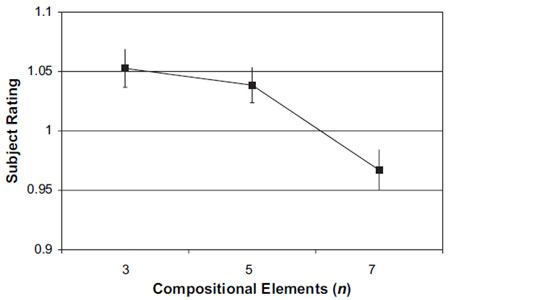

For the Web page images, our researchers found that "symmetry" had much less effect on aesthetic appeal than did the number of images. When the number of images exceeded 5, then the ratings of aesthetic appeal decreased in a statistically significant manner.

What was your prediction? Whether it was right or "wrong" does it now seem reasonable that like Goldilocks, trying out a variety of solutions may be your best bet to getting it "just right"?

Put briefly, there are some things you just cannot reasonably predict! So try them out and measure the response. The "magnitude estimation method" has strong inherent logic. That's one method to start with.

Figure 3. For experiment 2, participants rated Web page designs with 7 images lower in aesthetic appeal than designs with either 3 or 5 images.

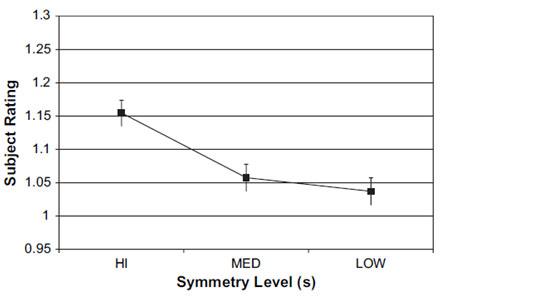

Figure 4. Experiment 1, without any text surrounding the images, participants gave higher ratings to layouts with greater symmetry.

More Goldilocks results from experiment 1

When presented with a more abstract design (without any words in the designs), Bauerly and Liu found that "symmetry" did indeed have an effect on subject ratings. They found that high symmetry received higher ratings as in this chart.

Could we have predicted this based on any prior experience? Probably not. In fact, this finding did not show up in Experiment 2 that used simulations of Web pages.

Now, you may never have "blank" backgrounds as in this Experiment 1. However, it is reasonable that your "background" elements are unique.

What's the moral here? Use the Goldilocks Principle: test, iterate, and test until "it's just right".

Let Goldilocks solve the problem of "wicked design"

In a sense, the design issues of symmetry and number of elements discussed above might be considered "grade school" problems for usability.

We get the idea very rapidly that we can generate solutions and try them out using measurements like the "magnitude estimation method" described above.

But what about that $4 million project for designing a new breakthrough killer-app your company needs in order to beat the competition for the next 2 years? And you have 6 months to do it.

To what degree can we stay with our old definition of iteration? Namely, can we live with "see how well it works, then make it better"? Some people call this the "tame problem" of design.

Let's look briefly at a case study of an IBM project, reported in 2006 by Wolf, Rode, Sussman and Kellog. They faced what they call a "creative design" problem (the wicked problem) versus our more typical "engineering design" problem (the tame problem).

In short, they define the "wicked problem" of creative design, as design that...

"is about understanding the problem as much as the resulting artifact. Creative design work is seen as a tight interplay between problem setting and problem solving. In this interplay, the design space is explored through the creation of many parallel ideas and concepts. The given assumptions regarding the problem are questioned on all levels. Creative design work is inherently unpredictable. Hence, the designer plays a personal role in the process." (My italics.)

The take-away here, again, is reframing our goals from "passing the test" to "getting it just right". So, we're back to the Goldilocks Principle as a guide to the toughest challenges of designs.

What are some methods that support the "wicked problem" of design? The quartet of authors suggest the following. (I recommend you skim their article for greater understanding of their profound points...)

1. Adopt a non-linear process of intent and discovery

Abandon hope for a linear, premeditated path of reasoning to solutions. Replace that with pragmatic assessment of the activities you conduct in order to invent and gain consensus.

Goldilocks tried out the bed, the chair and the porridge, because she was tired, wanted to sit at the table, and was hungry. She was a pragmatist.

2. Invoke design judgment ‚Äď a combination of knowledge, reflection, practice, and action

Where do leaps of creativity come from? They come from occasional abandonment of prior ideas of scientific validity. Instead of rigid adherence to method, the authors say "the designer practices the design process on behalf of the user in order to bring about purposeful change and meaning".

Goldilocks took a leap of faith when breaking into the bears' home. She had no idea who lived there. Her intrusion became the basis of new relationships and survival.

3. Make artifacts

Proof then comes from drawings, prototypes, and sketches that validate your design and "gain acceptance" of your solution among others.

Goldilocks was driven by curiosity. She had instincts for what was useful and had good reasons for checking out the bed, the chair, and the food.

4. Conduct design critiques

Conversation with peers who are versed in the field of your inquiry brings insight, accountability and opportunities to validate or restructure your direction and method. Include users and stakeholders, as well.

Without the three bears as conversational partners, Goldilocks would have missed the significance of her explorations. She made social inroads by talking to the bears!

Trust but verify...

We have toured a world of design issues. The Goldilocks Principle offers a new catchphrase that may embolden you and your colleagues to see your usability work in a new light.

I hope that is the case.

For the record, did our IBM authors ignore the iterative design and testing method? No, they didn't. They remind us that "user-centered design embodies aspects of both creative and engineering design... There is a place in computer human interaction for iterative development, with its prototypes and testing."

I suggest this advice tells us to "trust" our intuition but "verify" the outcomes in the case of "wicked" design problems.

Iterate but verify...

In the case of the "tame" design problems, we must still tread lightly to avoid rash conclusions.

As an example, I'll mention that the Bauerly and Liu study (above) was replicated by Liu and three colleagues at the Beijing Institute of Technology in China. (Yes, this is a cross-cultural test of the effects of symmetry and the number of page elements).

This test replicated the condition using the "blank" background while using black squares (Experiment 1 of Bauerly and Liu).

The results with Chinese participants replicated the American findings regarding a general preference for symmetry. However, the Chinese results also showed that a larger number of elements did not decrease the aesthetic appeal. Pages with 7 elements had the same aesthetic appeal ratings as groups of 5 and 3.

This contrasts with the American findings that showed pages with 7 elements tended to reduce the aesthetic ratings. The American study concluded this was probably due to the greater "density" or "complexity" of the design.

The China study concluded that Chinese users were less sensitive to the complexity of the interface than American users.

So much for generalizations. Remember "Iterate but Verify".

The Goldilocks Principle

Remember what Goldilocks said after testing the extremes of hot and cold, tall and short, soft and hard? She said: "This is just right".

How did she earn the right to say that?

She tried different things that made sense to her.

This is the Goldilocks Principle.

Go, build, try, and see whether it is just right.

References

Bauerly, M. and Liu, Y, 2008. Effects of symmetry and number of compositional elements on interface and design aesthetics. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 24(3), 275-287.

Bi, L., Fan, X., Zhang, G., Liu, Y., and Chen, Z. 2009. Effects of symmetry and number of compositional elements on Chinese users' aesthetic ratings of interfaces. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, accepted for publication.

Goldilocks Principle. Downloaded 29 July, 2010 from Wikipedia.

Wolf, T.V., Rode, J.A., Sussman, J., and Kellogg, W.A. 2006. "Dispelling design as the "Black Art" of CHI," Proceedings of CH, 2006 Conference (Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 22-27 April).

Message from the CEO, Dr. Eric Schaffer ‚ÄĒ The Pragmatic Ergonomist

Leave a comment here

Reader comments

Speider

Schneidersweb

An interesting and informative article on the emotion responses on the part of users, but as a designer, I have to point out that more often than not, testing is never done and design and usability is determined by the client and staff members, leading to the term, "design-by-committee."

If you remember the story, Goldilocks broke into a house, vandalized the place, stole food and ended up fleeing the scene of the crime and is still at large to this day.

Stan Lindstone

Nice to try to coin a term "formative testing" but basically in an iterative user-centered design process, testing during the design is just testing. Would we need now to coin the final usability test of a product "informative but futile testing"?

Subscribe

Sign up to get our Newsletter delivered straight to your inbox

Privacy policy

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

This Privacy Policy governs the manner in which Human Factors International, Inc., an Iowa corporation (‚ÄúHFI‚ÄĚ) collects, uses, maintains and discloses information collected from users (each, a ‚ÄúUser‚ÄĚ) of its humanfactors.com website and any derivative or affiliated websites on which this Privacy Policy is posted (collectively, the ‚ÄúWebsite‚ÄĚ). HFI reserves the right, at its discretion, to change, modify, add or remove portions of this Privacy Policy at any time by posting such changes to this page. You understand that you have the affirmative obligation to check this Privacy Policy periodically for changes, and you hereby agree to periodically review this Privacy Policy for such changes. The continued use of the Website following the posting of changes to this Privacy Policy constitutes an acceptance of those changes.

Cookies

HFI may use ‚Äúcookies‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúweb beacons‚ÄĚ to track how Users use the Website. A cookie is a piece of software that a web server can store on Users‚Äô PCs and use to identify Users should they visit the Website again. Users may adjust their web browser software if they do not wish to accept cookies. To withdraw your consent after accepting a cookie, delete the cookie from your computer.

Privacy

HFI believes that every User should know how it utilizes the information collected from Users. The Website is not directed at children under 13 years of age, and HFI does not knowingly collect personally identifiable information from children under 13 years of age online. Please note that the Website may contain links to other websites. These linked sites may not be operated or controlled by HFI. HFI is not responsible for the privacy practices of these or any other websites, and you access these websites entirely at your own risk. HFI recommends that you review the privacy practices of any other websites that you choose to visit.

HFI is based, and this website is hosted, in the United States of America. If User is from the European Union or other regions of the world with laws governing data collection and use that may differ from U.S. law and User is registering an account on the Website, visiting the Website, purchasing products or services from HFI or the Website, or otherwise using the Website, please note that any personally identifiable information that User provides to HFI will be transferred to the United States. Any such personally identifiable information provided will be processed and stored in the United States by HFI or a service provider acting on its behalf. By providing your personally identifiable information, User hereby specifically and expressly consents to such transfer and processing and the uses and disclosures set forth herein.

In the course of its business, HFI may perform expert reviews, usability testing, and other consulting work where personal privacy is a concern. HFI believes in the importance of protecting personal information, and may use measures to provide this protection, including, but not limited to, using consent forms for participants or ‚Äúdummy‚ÄĚ test data.

The Information HFI Collects

Users browsing the Website without registering an account or affirmatively providing personally identifiable information to HFI do so anonymously. Otherwise, HFI may collect personally identifiable information from Users in a variety of ways. Personally identifiable information may include, without limitation, (i)contact data (such as a User’s name, mailing and e-mail addresses, and phone number); (ii)demographic data (such as a User’s zip code, age and income); (iii) financial information collected to process purchases made from HFI via the Website or otherwise (such as credit card, debit card or other payment information); (iv) other information requested during the account registration process; and (v) other information requested by our service vendors in order to provide their services. If a User communicates with HFI by e-mail or otherwise, posts messages to any forums, completes online forms, surveys or entries or otherwise interacts with or uses the features on the Website, any information provided in such communications may be collected by HFI. HFI may also collect information about how Users use the Website, for example, by tracking the number of unique views received by the pages of the Website, or the domains and IP addresses from which Users originate. While not all of the information that HFI collects from Users is personally identifiable, it may be associated with personally identifiable information that Users provide HFI through the Website or otherwise. HFI may provide ways that the User can opt out of receiving certain information from HFI. If the User opts out of certain services, User information may still be collected for those services to which the User elects to subscribe. For those elected services, this Privacy Policy will apply.

How HFI Uses Information

HFI may use personally identifiable information collected through the Website for the specific purposes for which the information was collected, to process purchases and sales of products or services offered via the Website if any, to contact Users regarding products and services offered by HFI, its parent, subsidiary and other related companies in order to otherwise to enhance Users’ experience with HFI. HFI may also use information collected through the Website for research regarding the effectiveness of the Website and the business planning, marketing, advertising and sales efforts of HFI. HFI does not sell any User information under any circumstances.

Disclosure of Information

HFI may disclose personally identifiable information collected from Users to its parent, subsidiary and other related companies to use the information for the purposes outlined above, as necessary to provide the services offered by HFI and to provide the Website itself, and for the specific purposes for which the information was collected. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information at the request of law enforcement or governmental agencies or in response to subpoenas, court orders or other legal process, to establish, protect or exercise HFI’s legal or other rights or to defend against a legal claim or as otherwise required or allowed by law. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information in order to protect the rights, property or safety of a User or any other person. HFI may disclose personally identifiable information to investigate or prevent a violation by User of any contractual or other relationship with HFI or the perpetration of any illegal or harmful activity. HFI may also disclose aggregate, anonymous data based on information collected from Users to investors and potential partners. Finally, HFI may disclose or transfer personally identifiable information collected from Users in connection with or in contemplation of a sale of its assets or business or a merger, consolidation or other reorganization of its business.

Personal Information as Provided by User

If a User includes such User’s personally identifiable information as part of the User posting to the Website, such information may be made available to any parties using the Website. HFI does not edit or otherwise remove such information from User information before it is posted on the Website. If a User does not wish to have such User’s personally identifiable information made available in this manner, such User must remove any such information before posting. HFI is not liable for any damages caused or incurred due to personally identifiable information made available in the foregoing manners. For example, a User posts on an HFI-administered forum would be considered Personal Information as provided by User and subject to the terms of this section.

Security of Information

Information about Users that is maintained on HFI’s systems or those of its service providers is protected using industry standard security measures. However, no security measures are perfect or impenetrable, and HFI cannot guarantee that the information submitted to, maintained on or transmitted from its systems will be completely secure. HFI is not responsible for the circumvention of any privacy settings or security measures relating to the Website by any Users or third parties.

Correcting, Updating, Accessing or Removing Personal Information

If a User’s personally identifiable information changes, or if a User no longer desires to receive non-account specific information from HFI, HFI will endeavor to provide a way to correct, update and/or remove that User’s previously-provided personal data. This can be done by emailing a request to HFI at hfi@humanfactors.com. Additionally, you may request access to the personally identifiable information as collected by HFI by sending a request to HFI as set forth above. Please note that in certain circumstances, HFI may not be able to completely remove a User’s information from its systems. For example, HFI may retain a User’s personal information for legitimate business purposes, if it may be necessary to prevent fraud or future abuse, for account recovery purposes, if required by law or as retained in HFI’s data backup systems or cached or archived pages. All retained personally identifiable information will continue to be subject to the terms of the Privacy Policy to which the User has previously agreed.

Contacting HFI

If you have any questions or comments about this Privacy Policy, you may contact HFI via any of the following methods:

Human Factors International, Inc.

PO Box 2020

1680 highway 1, STE 3600

Fairfield IA 52556

hfi@humanfactors.com

(800) 242-4480

Terms and Conditions for Public Training Courses

Reviewed: 18 Mar 2014

Cancellation of Course by HFI

HFI reserves the right to cancel any course up to 14 (fourteen) days prior to the first day of the course. Registrants will be promptly notified and will receive a full refund or be transferred to the equivalent class of their choice within a 12-month period. HFI is not responsible for travel expenses or any costs that may be incurred as a result of cancellations.

Cancellation of Course by Participants (All regions except India)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (India)

4 Pack + Exam registration: Rs. 10,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (4 Pack-CUA/CXA) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Cancellation / Transfer by Participants (Online Courses)

$100 processing fee if cancelling within two weeks of course start date. No cancellations or refunds less than two weeks prior to the first course start date.

Individual Modules: Rs. 3,000 per participant ‚Äėper module‚Äô processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the course (any Individual HFI course) registration before three weeks from the course start date. No refund or carry forward of the course fees if cancelling or transferring the course registration within three weeks before the course start date.

Exam: Rs. 3,000 per participant processing fee (to be paid by the participant) if cancelling or transferring the pre agreed CUA/CXA exam date before three weeks from the examination date. No refund or carry forward of the exam fees if requesting/cancelling or transferring the CUA/CXA exam within three weeks before the examination date.

No Recording Permitted

There will be no audio or video recording allowed in class. Students who have any disability that might affect their performance in this class are encouraged to speak with the instructor at the beginning of the class.

Course Materials Copyright

The course and training materials and all other handouts provided by HFI during the course are published, copyrighted works proprietary and owned exclusively by HFI. The course participant does not acquire title nor ownership rights in any of these materials. Further the course participant agrees not to reproduce, modify, and/or convert to electronic format (i.e., softcopy) any of the materials received from or provided by HFI. The materials provided in the class are for the sole use of the class participant. HFI does not provide the materials in electronic format to the participants in public or onsite courses.